Original article: 145 años dela ciudad de Temuco: La otra historia de una fundación marcada por la invasión y el despojo mapuche

The Pomona Massacre, Forced Displacement of Communities, and Profanation of Ancestral Cemeteries: Key Events that Defined the Foundation of Temuco in its 145 Years

Amid flags and official celebrations, Temuco marks 145 years since its founding as a city established by the Chilean state. However, behind the protocols and anniversary speeches lies an uncomfortable truth that authorities have preferred to keep in the shadows: the city was not born from a civilizing pact but from a military occupation that brought massacres, forced displacements, and the systematic usurpation of territories that had belonged to Mapuche communities for centuries.

The foundation of Temuco in 1881 fits within the context of the so-called «Pacification of Araucanía,» a military campaign that annexed ancestral lands to the nation-state. What official reports from the time referred to as the «incorporation of new territories» meant land loss for the indigenous communities and the start of a diaspora still seeking justice today.

As 145 years have passed since that landmark event, the wound of occupation remains open, challenging society to look beyond the anniversary and ask whether it is possible to celebrate a past that still hurts.

What follows is an article based on the writings of communicator Alfredo Seguel and indigenous leader Benigna Troncoso Rucán, a descendant of the chief Huete Rucán.

Temuco: 145 Years of Blood and Silence – A City Built on Mapuche Dispossession

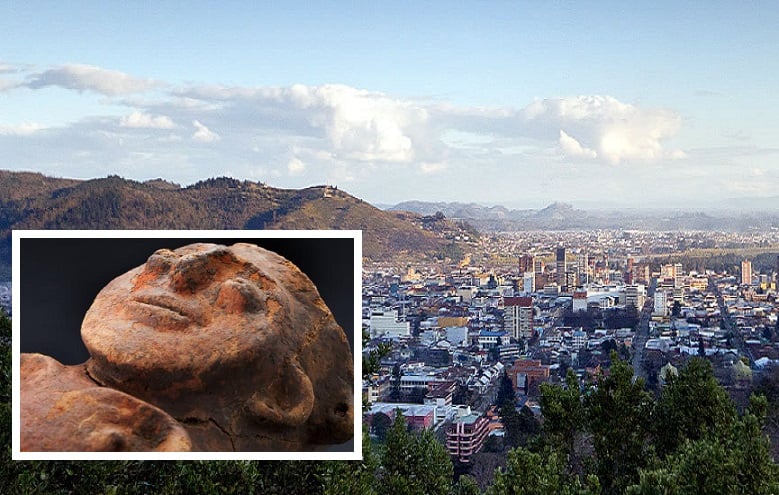

The regional capital of La Araucanía officially commemorates 145 years. Flags, formal speeches, and artistic events will mark the anniversary of a city that now surpasses 300,000 inhabitants. Yet, beneath the festive tone promoted by authorities, an uncomfortable truth remains obscured by textbooks and official celebrations: Temuco, much like various other towns south of the Biobío River, was not established through a civilizing pact but through a military occupation involving massacres, forced displacements, and systematic profanation of sacred sites for the Mapuche people.

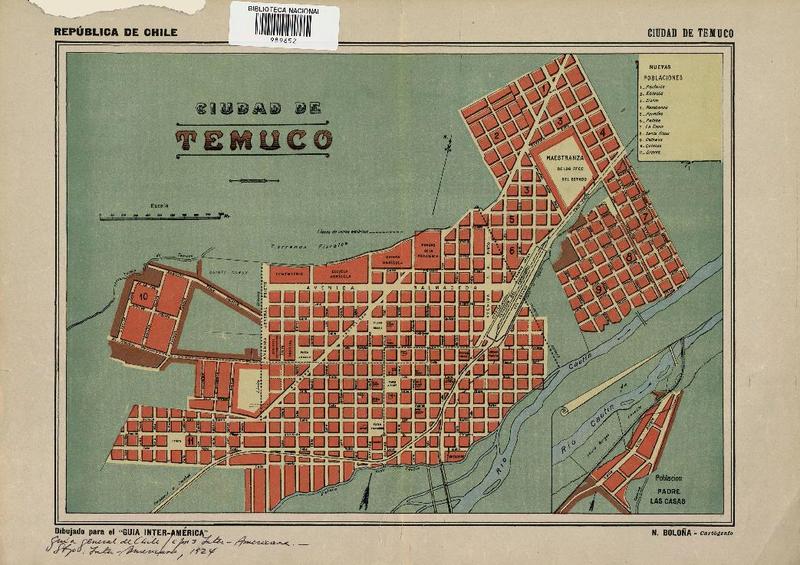

Thus, on February 24, 1881, by order of Interior Minister Manuel Recabarren, the Chilean Army established a military fort in lands that had belonged to Mapuche families for generations. The founding ceremony wasn’t a peaceful act but rather a show of force aimed to intimidate the Mapuche groups resisting occupation.

“At the end of the parliament, the troops executed a series of maneuvers and drills while machine guns were fired towards Mount Ñielol. The Mapuche watched in astonishment while being informed that these were the weapons that had defeated Peru,” recounts Oscar Arellano’s book, “Fiftieth Anniversary of Temuco (1881-1931).”

Among the leaders who resisted were the lonkos Lienan and Huete Rucán, the very owners of the land where the city now stands. Their resistance to protect their territory was met with gunfire.

The Pomona Massacre:

One of the most brutal episodes during that occupation occurred near the Cautín River, in an area that today includes Avenida Costanera, Quinta Pomona, and the Los Pinos Spa. A 2024 investigation on the “Mapuche Routes of Memory” documents what official historiography has omitted for decades.

“This place of memory originates from the military events that unfolded on the soils of Temuco, dating back to the founding of the military garrison in February 1881,” states the text. It adds: “The Temukoche and their allies, after negotiating and asking the invading soldiers to leave, initiated hostilities when they refused to withdraw from the site. On the battle day, while attacked by a combined force from various allied territories, the soldiers staged a bold surprise attack on a Mapuche line camping in what is now Quinta Pomona, resulting in the deaths of two of their leading lonkos alongside their captains and kona, summing nearly a hundred casualties.”

One hundred Mapuche lives lost—one hundred names absent from anniversary speeches. One hundred stories buried beneath the concrete of a city that rose on their remains.

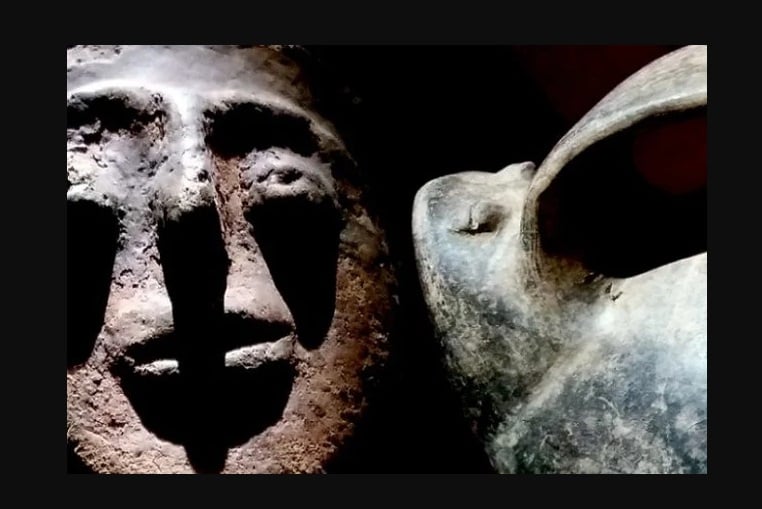

Paradoxically, 145 years after this history, near the original point where the city of Temuco was founded, recently unearthed Mapuche archaeological remains were discovered while constructing the Regional Library of Araucanía, adjacent to Plaza Recabarren and the Tucapel Regiment, on Vicuña Mackenna and O’Higgins streets.

The Profaned Sacred Territory: Ancestral Cemeteries Beneath the Asphalt

Numerous prior archaeological findings confirm that the land on which Temuco stands was, for centuries, a ceremonial and funerary space of extraordinary importance for the Mapuche people. A 2021 study reveals that during the 1960s and 1980s, “rescue” efforts were made on several cemeteries and funerary contexts throughout the city.

In 1984, at the Technological High School (formerly Industrial B-22) along Avenida Balmaceda, human remains and Pitrén-style ceramics linked to Mapuche burials were discovered. Archaeologist Américo Gordon documented sites like Ñielol 1 and Ñielol 2, where burials and monochrome ceramics were found. “This is a burial site of considerable dimensions,” noted the report.

One year prior, in 1983, Quinta Santa Elvira revealed funerary urns containing Valdivia ceramics from the late pre-Hispanic pottery period. “Both pieces contained human bones, but these were either destroyed or collected by local individuals,” detailed the study.

Mount Ñielol, named after a protective spirit (Ngen), formed part of an ancient ceremonial complex that included a large eltún (funerary space) spanning from the current Temuco cemetery (Prieto Norte with Balmaceda) to the grotto of the Virgin. Today, much of that sacred territory lies beneath buildings, streets, and plazas.

“My Great-Grandfather Owned the Lands Where Temuco Stands”: Testimony from Benigna Rosa Troncoso Rucán, Descendant of Chief Huete Rucán

Among the families most affected by the founding of Temuco is that of chief Huete Rucán, an ancestral authority who owned vast lands in what is now the city’s heart. His great-granddaughter, Benigna Rosa Troncoso Rucán, president of the Rucán Indigenous Community, vividly narrates the story of dispossession that has marked her family for generations.

“I must start by saying that this entire account is oral history, told by my mother Rosa Rucán, who was born in Molco, Pitrufquén, in 1922, daughter of Juan Rucán born in Temuco in 1887, a descendant of chief Huete Rucán. Owner of the lands usurped by the Chilean State to establish the city of Temuco,” declares Troncoso Rucán in a document shared with the Nor Fën Educational Space.

The Mapuche leader emphasizes that the borders of the territory were clearly defined: “It is well known that the boundaries of Mapuche territory were clearly established in parliament and meetings with ancestral authorities such as Chiefs and Lonkos with the Spanish Crown.”

“My great-grandfather chief Huete Rucán was tenaciously defended by one of his wives named Panchita Ferreira, who was heard at the time as she was NOT Mapuche,” she recounts, referring to a Chilean woman who, being part of the community, became an advocate before military authorities.

The Escape Across the Cautín River: The Forced Exile of the Rucán Family

The resistance of Huete Rucán had devastating consequences for his family. His son Juan Rucán, who was still a small child, had to flee to save his life.

“My mother Rosa Rucán tells us that my grandfather Juan Rucán, while still a small child, was pursued by Chilean invaders and to save his life was forced to flee Temuco. He fled with my grandmother, riding a horse and swimming across the Cautín River, gripped by fear and resigned to the genocidal power of the Chilean State,” narrates Troncoso Rucán.

The persecution was not an isolated incident. Historical records state that Huete Rucán had been identified as one of the main leaders of the resistance. Eduardo Pino’s book “History of Temuco” (1969) explicitly mentions him: “The main leaders of the uprising included: Melin of Rielol; Millapan of Cholchol; Necul Painal of Carirrifie; (…) and Huete Rucán of Catrimalal, who saved his life when facing the firing squad thanks to the tears of his wife, the Chilean ‘captive’ Panchita Ferreira.”

In November 1881, Commander Cartes captured chief Huete Rucán for being a “staunch opponent of ceding his lands.” His ruca was located where the new Municipal Market is currently being built, while chief Lienan’s was where the Hotel de La Frontera and Plaza Anibal Pinto (Plaza de Armas) now stand.

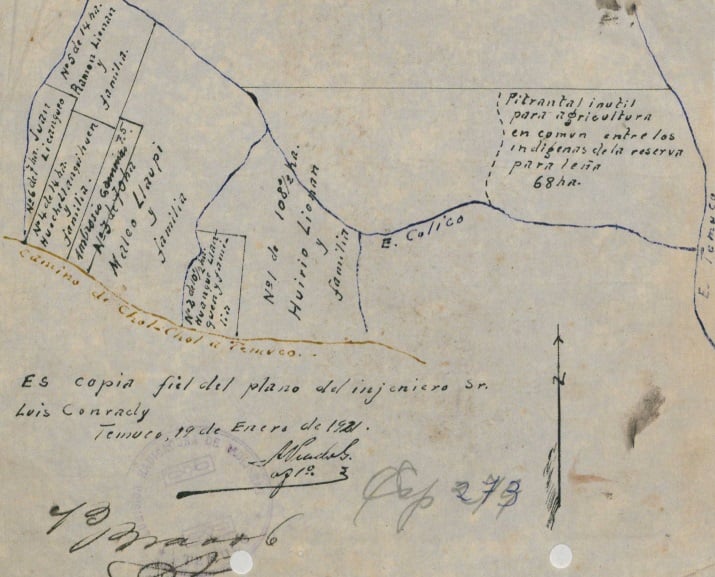

The Title of Merced That Did Not Prevent Dispossession: 430 Hectares for 87 Families Who Never Possessed Them

In 1894, as part of the settlement process instigated by the Chilean state, Huete Rucán, far from his habitat, was assigned a Title of Merced (No. 299) that supposedly recognized 430 hectares in the Ralun Coyán sector for him and 87 families. However, this measure came too late and proved insufficient.

“In that settlement, he was assigned a Title of Merced numbered 299 of the year 1894, supposedly awarded to him for 87 families over plot No. 145 of 430 hectares in the Ralun Coyán area of Temuco,” details Troncoso Rucán.

But the paper acknowledgment did not prevent family dispersal. Juan Rucán, the chief’s son, had to flee to unfamiliar lands, away from his beloved ñuke mapu (Mother Earth). He died on February 13, 1937, in Molco, Pitrufquén, at the age of 50. His daughter Rosa, Benigna’s mother, was orphaned at the age of 15.

“She was left to work as a domestic servant for a family of German settlers, where she grew up and later returned to her ruca and married my father. Together they worked their entire lives as caretakers in different areas of the fields owned by the settlers who had become the new owners of our cherished mapu. Thus, my three siblings and I grew up facing the challenges of having been dispossessed of our ancestral land in Temuco,” she recounts.

“My Mother Died with Hope for Justice”: A Struggle That Transcends Generations

Rosa Rucán, the daughter of the dispossessed chief, kept her family’s memory and the fight for their land alive until the end of her days. During Patricio Aylwin’s administration, the first democratic government after the dictatorship, the Mapuche leader sought unsuccessfully to be heard.

“My mother continued the relentless fight for her lands. During President Aylwin’s time, she approached him directly with a request regarding her lands, yet received no positive response. My mother passed away on July 16, 1996,” Benigna recalls.

The fear of abuse and discrimination left deep scars on the cultural identity of the family. “My mother Rosa felt a lot of fear for all that happened and avoided teaching us her language and maintaining Mapuche culture, out of fear of discrimination in schools and at work. The invading Chilean people left profound marks on our family, suffering from the dispossession and subsequent founding of Temuco on February 24, 1881, right in the heart of their precious mapu,” admits Troncoso Rucán.

Today, the descendants of chief Huete Rucán live dispersed in the same city that belonged to their ancestors. On December 17, 2015, with legal entity No. 2147, the Rucán Indigenous Community was established, consisting of 22 individuals seeking to keep the memory alive and demand some form of reparations.

The Present of a Debt: Descendants Pay High Rents on Lands Once Belonging to Their Family

The paradox faced by the descendants of Huete Rucán is as cruel as it is illustrative of the dispossession endured: they currently must pay rent to reside in the territory that ancestrally belonged to their family.

“Today, twelve of fifteen members pay exorbitant rent to live on land that used to belong to my ancestors,” denounces Benigna Troncoso Rucán.

The scale of the dispossession is so great that there have not even been minimal gestures of reparations, such as granting a stall in the new Municipal Market for the community to sell their products, or symbolic recognition by naming a street or plaza after chief Huete Rucán, where thousands of people pass daily unaware of the legacy upon which the city stands, have been considered by the authorities in these 145 years.

“My mother died with the hope that we, her daughters and sons who carry her blood and surname with pride, could continue this task: the quest for justice for ourselves as rightful descendants and also because our ancestors were cruelly massacred, and there is no place in Temuco where their remains can be found, as where the cemetery used to be now lies a massive concrete structure, streets, buildings, and plazas,” concludes Benigna Rosa Troncoso Rucán.

)